I’m often amazed by the discussions—or absence of discussions—on differentiation. In order to win, we have to differentiate our solutions, but we have to differentiate them in the areas the customer cares about.

Most of the time, it’s long lists of features, comparing our solutions to the competition, with the goal being more boxes checked in our column than the competitor’s. We overwhelm and confuse customers with long lists of features, benefits, and whatever we can.

But when we differentiate ourselves, it’s critical to focus on what the customer cares about. Everything else is meaningless—and, in fact, wastes the customer’s time.

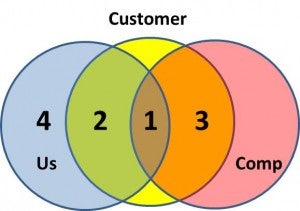

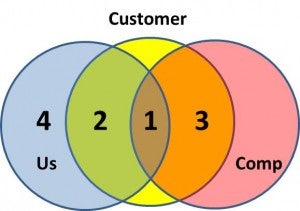

Let’s look at the example below. We can represent the customer’s needs and requirements as the center yellow circle. We can represent our capabilities as the blue circle, and the competitor’s as the red circle.

We probably never address 100% of our customers’ requirements. Neither do our competitors. If one or the other of us did, customer decision making would be much easier, but in reality no one ever does meet 100% of the customer requirements.

Both we and our competitors address a certain number of common customer needs (area 1 in the illustration). We aren’t differentiated in that area, so we are wasting our time and the customer’s time focusing on those issues. We are differentiated in area 2, while our competitors are differentiated in area 3.

So how do we win?

First, we have to prioritize the customer’s needs and requirements. We have to understand what’s important to them and why. Looking at the illustration, we are differentiated and advantaged in area 2. Our competitor is differentiated and advantaged in area 3.

Second, we have to understand their perceptions and attitudes about our solutions and the alternatives. How well do we address the needs, how well does the competition (or alternatives)? The degree to which the customer’s priorities are in areas 1 and 2, advantage us. The degree to which the customer’s priorities are in areas 1 and 3, then our competitors are advantaged.

If we can’t influence our customer’s priorities, shifting them into areas 1 and 2, our probability of winning is very low. If the customer doesn’t view their requirements in area 2 as the most important, then we aren’t differentiated; at best we are equal to our competitors.

But what about area 4 in the illustration? It’s an area that we have to be careful about, but where too many sales people make serious mistakes. Perhaps we can get the customer to look at the problems differently. Perhaps we can get them to expand their needs—identifying items in area 4 that are important and moving them into area 2.

It’s a great strategy, but we have to do this early in the sales cycle—perhaps it’s the insight we bring the customer. Perhaps it’s the thoughtful conversations early in their buying cycle, just as they are determining their needs, requirements, and priorities.

The error we make is not understanding, driving, or helping the customer define their requirements or priorities. The error we make is getting engaged too late, when they’ve already set their priorities. Yet we waste their time, and ours, by parroting our long list of features, functions, and capabilities. They care about (1) and (2), but (4) is meaningless and wastes their time.

Do you understand your differentiation from the customer’s point of view? Are you influencing the customer in the right ways, to maximize your ability to differentiate yourself? Are you helping the customer shape their needs and priorities?

This article was originally published by Partners in Excellence

Published: November 7, 2013

3035 Views

3035 Views