What if Managing Your Team Meant Solving Homelessness?

By: Bill Yates

Sometimes, project management can mean managing stakeholder relationships along with managing your team, and the complexities of marrying those two needs.

In this Manage This podcast transcript, we delve into the development of temporary living shelters, whether as a result of natural disasters or homelessness. You can listen to the full episode here or read on:

AMY KING: So there’s this really popular American narrative, which is homelessness is a housing problem. I 100% disagree with that. … A house, four walls and a roof, do not solve a person’s homelessness crisis. Giving them keys to an apartment does not solve their homelessness. You have to address the root cause issue. That person will end up homeless again.

WENDY GROUNDS: Our guest is Amy King, and she is the founder and CEO of Pallet. This is a public benefit corporation working to end unsheltered homelessness and give fair chance employment opportunities to people of all backgrounds. Pallet has deployed more than a hundred villages across 85 U.S. cities. Amy also co-founded Weld Seattle, which is a nonprofit that equips systems-impacted individuals with housing, employment, and other resources conducive to reintegration back into society. And her passion is just incredible. I think you’re really going to enjoy her story.

BILL YATES: Yeah, when you take a husband and a wife – and Amy has a background in psychology. She is a psychologist by education. Her husband is a master builder engineer. When you take those two and combine them and take the passion they have, you end up with something amazing like Pallet.

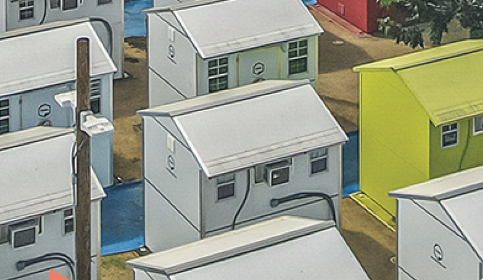

Just getting back to it, Pallet offers short-term shelter, community rooms, and private stall bathrooms. A large interim housing community can be set up in a matter of days with minimal tools using this Pallet system. Each Pallet structure is versatile. Units can be used for a variety of purposes from sheltering evacuees to building command-and-support centers or for temporary housing for recovery workers. Their motto is “No one should go unsheltered when shelter can be built in a day.”

WENDY GROUNDS: And they’ve done so much more than just build shelters. When you hear Amy talk, what started as a small project, it grew, and it became more and more, and they got involved in the community. They got involved in the lives of the people who were living in these shelters.

BILL YATES: And as we’ll hear from Amy, many of those that have experienced homelessness are now vibrant workers and contributors to Pallet.

WENDY GROUNDS: Hi, Amy. Welcome to Manage This.

AMY KING: Thank you so much for having me. I’m excited to be here.

Meet Amy

WENDY GROUNDS: We are really looking forward to getting into this topic and to hearing about the incredible work that you’re doing. But won’t you first tell us a little bit about your background, your career, and how it led to fighting homelessness?

AMY KING: Yeah, absolutely. So I actually studied psychology in school. And I started out as a psychologist working primarily with children, and then moved into the healthcare space and managed some surgical practices here at our local Level 1 trauma center called Harborview. And then I did private practice for a while, so more on the business side of healthcare. And I learned a lot about business and kind of fell in love with business.

At the same time, my husband, he’s a general contractor and has been for 20 years. And so he started a construction company that we ended up very much by accident hiring people that were exiting the justice system to work in that organization, working with them, teaching and training them on the construction trades. And my husband asked me to come work with him and help him sort of build out the business components of that entity, which I agreed to do, temporarily because I like being married to him. I said, “I’ll do it for a while, and then I’m going back to healthcare.” And then I just really fell in love with the people that were working with us, and I never left.

So they really spurred us on to think about homelessness, addiction recovery, and justice system involvement, and kind of how that impacts people’s lives. And Pallet, and we also have a nonprofit called Weld Seattle, those two entities were born out of that original entity. So that’s kind of the wavering path I’ve been on since I got out of college. Yeah.

The Homeless Problem

BILL YATES: You developed Pallet because you saw a problem. Can you describe the homeless problem that you observed in your community?

AMY KING: Absolutely. Yeah, when we started Pallet, you know, homelessness was really on the rise. And it’s been a problem for a long time. But public homelessness was really on the rise, and especially in cities like Seattle, where we’re from, where camping bans went away, and people were more publicly out in the open, and you could see them. And the issue was more kind of in your face.

And as we saw it and interacted with those folks, and we’re also employing people who had experience with living on the streets, we were learning a lot about trauma and how that kind of institutes these sorts of issues. We learned a lot about broken societal systems and how they impact our ability to help people and respond to people. And as we learned more, we just realized we couldn’t look away, and we couldn’t not do anything.

Since then, of course, homelessness has really been on the rise, but being able to center voices of lived experience and spend our time around folks who have actually lived this way and learning from them has really shaped our response efforts, both from a product perspective and a model perspective. And it’s been quite a learning curve for us.

Homelessness Data

WENDY GROUNDS: Do you have any data on homelessness?

AMY KING: Yeah, I have so much data on homelessness! You may have seen the most recent PIT Count that came from the National Alliance to End Homelessness and the US Interagency Council on Homelessness. As of 2022, which is the most recent data, there were five hundred and eighty thousand people experiencing homelessness across the US. About forty percent of those live unsheltered. So they are outside or living in an uninhabitable situation, on the street, under a tarp, in a building that isn’t meant for human habitation.

Interestingly enough, it’s important to know who the population is and characterize the population. We know that the data we have is not overly reliable and valid. But of the data we have, it shows that about seventy two percent of people experiencing homelessness are individuals, so individual adults that are living alone or have been estranged from their families.

About twenty-eight percent are families. And about twenty-two percent of the folks that are experiencing homelessness are chronically homeless, meaning that they’re cycling through systems and they just stay outside and they’re struggling to get them engaged with services and move on.

We also know that the vast majority of people experiencing homelessness in America are people of color. There’s a large percentage of people that are LGBTQ, transgender youth, that’s a really high population. And then, males more than females, so a lot more men than women are experiencing homelessness especially unsheltered homelessness. So those are some of the high data points to know. Predominantly transient adults is who we serve though Pallet and who really fits our model well.

Designing the Shelters

WENDY GROUNDS: Tell us a little bit about the homes that you’ve developed, because I read on your website that you developed these homes out of Hurricane Katrina when you saw a need for people needing rapid shelters. And now this has become also shelters for homelessness. So just tell us about the actual homes that you’ve developed.

AMY KING: Yeah, so my husband, again, he was the original inventor. He’s a general contractor so understands very much what it takes to build housing from a construction perspective. After Hurricane Katrina he said, “It’s crazy to me that in the wealthiest country in the world that we crammed a bunch of people into the Superdome, and all of the health and safety issues that came out of that experience that were all over the news.”

And really what it boiled down to was this idea of agency and independence of personal space, but with services. And so it felt like we should be able to provide individualized housing post-disaster that allows people to feel safe and secure and not like they’re being exposed to health issues, which is of course even more relevant now because of COVID.

But at the time, he felt like we should be able to do this better. So he created the concept of a panelized shelter system, understanding that panelized construction is easier to deploy, it’s more cost-effective, strips out a lot of the costs that you get with general construction. So we were very intentional with the design from a disaster response perspective. But then we sort of – we got busy with other things and didn’t really pursue it.

And then as I mentioned before, once we started working with folks with lived experience, and homelessness was growing, and we said, “Hey, what is it from your perspective that’s missing from the response landscape for people that are experiencing homelessness?” And they said, “The agency of choice and individuality of space. People don’t want to go to congregate shelters.” And you’d hear that on the news all the time back then, you still hear it now, people that don’t want help or they’re refusing services. And the general assumption is, you know, people want to be homeless.

That’s not true. I’ve never met a single homeless person in my experience of doing this work that said, “I really want to be here, leave me alone.” They just don’t want the services that are being provided because they’re undignified, and they can’t bring their pets. They can’t stay with their partner, they can’t keep their things with them, they feel unsafe – a variety of reasons why they didn’t want to go to congregate shelter.

So as we learned about this, we said, well, you know, we took this design that my husband had created, took it to our folks with lived experience and said, “Do you think that this model would be useful for homelessness?” And they were just blown away. They were like, “This is exactly what’s missing. We have to build this. It makes sense.” And people need the dignity of their own space, and we think that people will engage with services if we go forward with this.

So we really have learned a lot about the population, and kind of what their needs are, and felt at the time like this was the right solution. And then there was a long journey to getting others to believe that.

Looking at a Pallet Home

BILL YATES: One thing, Amy, I want you to describe, kind of build a mental picture for our listeners. Help people understand what does a single unit look like.

AMY KING: Sure, yeah. So the shelters themselves are a panelized construction. They go together in under an hour. So we prefabricate the panels here in our shop. Each of the panels is made of aluminum structural members and then a composite wall material. This is really important because it’s a non-organic material that’s mold, mildew, rot resistant, bed bug resistant. It’s washable and sterilizable. So you can reuse this product over and over again. It’s a very simple kind of stripped down version of a sleeping shelter or a bedroom. It has a locking door. It has windows. It has a cute little pitched roof and all the things.

So it kind of looks like a tiny house, although I don’t really like that term. It has beds, shelves, an electrical panel with a heater and an air conditioner. So all your basic things that you need to feel comfortable and safe. But it’s also stripped down enough to be functional and reusable and cost effective, which is the point. We also want it to elicit that engagement in the recovery process. So it’s pretty stripped down and simplified. But it looks like a small house.

The Prototyping Phase

BILL YATES: One of the pieces that is fascinating to me, Amy, is the whole process that you and your husband went through to develop these single units. So talk to us about that prototyping because there are a lot of lessons learned for project managers, prototyping is so important. You guys knocked it out of the park with that. How did you do that?

AMY KING: Yeah, thank you. I will say, I don’t think we knocked it out of the park, but I appreciate you saying that. But we are learning; right?

BILL YATES: Looks like it now.

AMY KING: We are learning and growing. Yeah. So I would be remiss if I didn’t note that we had an amazing engineer at the beginning, and this is truly a family business. He is my dad and was an engineer his entire life and career. He’s now retired, but he helped us from his engineering perspective really take Brady’s idea. Brady’s my husband, sorry, I should say that. He took my husband’s idea that came out of the Hurricane Katrina conversation we had and conversations with our folks and created an actual physical product.

Our product has since that time gone through probably eight or nine iterations. I often say, and one of our big mottos here, is the pursuit of perfection can be the enemy of progress. And in this particular situation, we felt like homelessness is a crisis and a disaster that needs to be addressed as such with speed and at scale. And because of that, we knew we were going to put out an imperfect product and then learn and grow and iterate.

So we intentionally built a team of in-house engineers to help us make those adjustments on an ongoing basis as we learned from end users and customers that were using our product. So our first prototype looked nothing like what you see today at all, completely different, different materials, different shapes, everything. We put it out in the field with our very first customer, the city of Tacoma, and it’s done well. It’s still up, that site. It’s still working.

But we learned a lot about the weaknesses of the materials we originally chose. And of course, with innovation across the country, we’re seeing new material types coming out all the time, new ideas. So we want to be agile and adapt to that evolving marketplace to get the best possible product that’s still cost-effective, but meets the needs of the end users.

So we are constantly creating new things and prototyping and testing. We have a team of third-party structural and thermal engineers that help us assess our product and test it on a regular basis to make sure that it’s structurally sound, it’s safe for people to sleep in, and that it meets basic needs. So there’s a whole engineering process that we go through consistently. And I’m very excited to tell you that our most recent review of survey results from end users and customers has spurred on a whole new line of products that we’re launching in about a week. So you’re the first to know. We’re super excited about it.

BILL YATES: Yeah.

WENDY GROUNDS: Yeah, that’s cool.

AMY KING: Yeah, keep your eye on the website.

Pitching the Project

WENDY GROUNDS: Yeah. Now, you had developed your project, and you knew there was a need, but you needed to incorporate some people, some stakeholders. So how did you pitch this?

AMY KING: Yeah, so this has been quite a journey for us, understanding the political climate around this issue. Stakeholders come from all places; right? So in order to address homelessness, we really need everyone at the table. So this includes elected officials, government agencies, nonprofit service organizations, business communities, and then just the broader community at large. So every time we go into a new city or region, certainly as you know there’s NIMBYism. There’s also now YIMBYism, which is the Yes in My Backyard movement, which we love. So you get a lot of conflicting views and concerns and ideas about how to address homelessness or human displacement.

So a big part of what Pallet does is coalition building. Whenever we come into a new area, we go to find who those stakeholders are. We work hard to bring everyone together to one table so that we can maximize resources, understand where any boundaries or issues, barriers might be, and then creating strategies to overcome those things. But the stakeholder group is quite large. Everybody has an opinion about homelessness, as I’m sure you know. And a lot of those opinions are very valid and formed on real life experience. A lot of people are fearful. That comes from a place of bad experience with someone or just general fear of the unknown. So we want to validate that, but also help people move past it so that we can solve it.

The First Client

BILL YATES: And you mentioned Tacoma was your first client, the city of Tacoma. How did you guys pitch that successfully? Because they had to be looking at you, going, “You’re going to do what? Can I see it?”

AMY KING: Yeah, yeah. It was an interesting story, actually. So again, we initially came up with this concept as a disaster response modality. So when we first got our prototyping done, we thought, let’s take it – before we try to tackle the beast that is homelessness response, let’s take it to a disaster response show and see what the reaction is. So we actually did a local disaster response trade show. We took the unit there. The City of Tacoma Emergency Management team was present and saw the product and fell in love with it and the concept. And we pitched it to them as an emergency management tool. They said to us, totally unsolicited, “We are about to declare a state of emergency around homelessness in our city, and we think that this matches.” And there is a huge crossover between disaster response, emergency management, and homelessness response now because of the volume of the crisis.

So that was the first time. This was in 2017, so before everything was really escalating. And they were one of the first cities that I’m aware of to declare this emergency response and then move with emergency funding and resources to create some sort of response tool. We were part of that and invited to participate in that table and discussion to figure out how to move their city forward. We set up a stabilization site in partnership with them, and it’s still up today and has been very successful. Our pitch today looks very different than that because we’ve learned a lot now, but that was our first pitch.

Talk to People with Lived Experience

And I will say, too, that it has changed a lot because back then – this was pre-COVID; right? We knew that the model that we were putting out there would be more effective because it was informed by people with lived experience. Back then, talking to people with lived experience was not popular. It was not a commonly done thing. So when we came to cities and said, “We know this is going to work because people with lived experience told us that,” they said, “What do you mean? Where are the experts? Where are the PhDs and the academia?” And we said, “We don’t agree that that’s the right way to go.” City of Tacoma was the first city to say, “We believe you, and we like this model that you’re listening to people with lived experience.”

Of course now, today, it’s like the popular thing to do. Everybody has people with lived experience, which is great, and we are thrilled that the culture has moved in that direction. But city of Tacoma was the first city to really grasp onto this idea of, “People who have been homeless probably know how to solve this problem. Let’s center their voices and understand what works.” And it’s still working today.

Impact Stories

WENDY GROUNDS: Now, when you talk to these people who have been homeless, and they’ve been living in a Pallet village, what impact has it had on them? Can you share some stories?

AMY KING: Yeah. So we’ve heard a lot of amazing stories. And if you go to our website, we have an awesome blog and a great marketing team who have told some of the stories of folks who’ve lived in our shelters. You know, we’ve had the privilege of meeting tons of people who were sleeping in their cars. I think that there’s one woman in particular that lived in L.A., she was sleeping in her car with her son who has a disability, and they had nowhere to go. I believe they were escaping domestic violence, if I remember correctly. And they had nowhere to go, and they were picked up by a local intake person and outreach person in the city of L.A. and brought to the Pallet Shelter community there, the very first one that we had. We now have, I think, 15 in L.A.; but this was our very first one.

And she lived there with her son for about three months, and during that time, because she was in a place where she could go back to every night, she could leave her things. She could go get a job. She had an address so she could go apply for employment. And three months later she got placed into affordable housing. She was able to get a job. Today, she’s employed, living in an apartment. Her son has the services he needs, and she’s doing fantastically well now. So we hear stories like that all the time for folks that are sort of temporarily displaced and just need some help.

We also have great stories of folks who have been homeless for 10, 20, 30, 40 years, so chronically homeless, struggling with mental health and substance use issues. We have one gentleman in particular who, I believe he lives in Colorado. He finally was willing to come inside because he had a pet, and that pet was his kind of emotional support animal. You typically can’t take pets to congregate shelters, so he was able to move into a Pallet community that had a dog run and services for pets, as well. He really stabilized there because he was able to work with a service provider. He’s now taking the appropriate medication for his mental health challenges. He’s been able to go to detox and get clean. And he spent about nine months, I believe, in one of our sites and has now moved on to a permanent apartment, has a job, is connected with his community again. So we see stories like that all the time.

Returning Home

The other one I’ll share that I think is really important is we are more often than not seeing folks that are experiencing homelessness return home to their families, which is something that most Americans don’t think about, and myself included. When you walk past someone on the streets, it’s common to think that person is alone because homelessness is an extreme form of isolation. And so the concept or the thought is that person needs a permanent supportive housing unit because they’re alone, and they have nowhere to go.

And what we’re finding is actually the vast majority of people who come to Pallet sites belong to someone. They’re a child, they’re a parent, they’re an aunt, an uncle, a cousin. And if they can stabilize and address whatever their root cause issue is that led them to homelessness, they can often return home as long as it’s a safe space for them and their families.

And it’s really been a beautiful experience for us to see and experience these family reunification stories, families that have lost touch with their family members over years and years. And once they stabilize, we’re able to help them, or the service providers are able to help them find their way back home. And I think that’s important to note that people belong to people. They have home communities they can return to. We need more mental health and addiction recovery services to help people get there.

BILL YATES: This is intriguing to me. I think of projects that I’ve worked on in the past where I thought I knew what the benefits of our product or service were going to be. I had no clue. And I’m hearing this from you, it’s like they’re big aha moments. So yeah, it must have been amazing for you guys. And it’s funny because Amy, you mentioned that the pitch has changed. I’ll bet it has. It’s like, hey, here are the benefits. Now, I don’t want to talk about our benefit list two years ago. Let’s talk about what we know now.

COVID as a Catalyst

AMY KING: Yeah, well, and it’s been interesting to see, I mean, I say this a lot, but COVID was actually a catalyst for growth for Pallet. So while many other businesses were winding down or struggling to keep people employed, we were deemed essential because housing for people that were unhoused was really important during that time for health and safety measures. And we exploded with demand. So cities that were struggling to talk to us because they couldn’t understand the benefit of this model, they were suddenly forced to initiate this model because they needed to separate people for health and safety reasons. So congregate shelters started clearing out, and cities were like, what are we going to do? Let’s call Pallet.

So we were crazy busy during COVID. But what happened as a result of that sort of health, public health reasoning for Pallet sites is we got to prove the efficacy of the model. So people got to see more people that are traditionally service diverse are coming inside because they can bring their pet, their partner, their things. They have a place to stay. They’re getting jobs. They’re getting access to services. They’re exiting faster and more efficiently and more sustainably. They’re staying housed after they leave.

So the model proved itself. What we knew to be true from our people with lived experience was actually proven because of a public health crisis; right? Which, you know, homelessness is, too, by the way. But I think it’s interesting to note that the pitch changed because it became a public health issue. But then it became, look how good this works. Let’s keep doing it now because we know it’s better than congregate. And now we have the data to show that it’s effective.

The Impact of a Pallet Village

WENDY GROUNDS: What stands out to me is you started just building a little structure that somebody could use in a disaster or disaster of homelessness, but it’s become a village. I mean, you offer social services. You offer so much more. There’s, a laundry. There’s bathrooms. There’s all sorts of things. Can you describe kind of what a village does?

AMY KING: Yeah, absolutely. So we do require that our products be set up in community settings. We never sell a single shelter to a single person right now because again, you know, homelessness, addiction, incarceration, those are all extreme forms of isolation. And the best way to move people into rehabilitation is to embed them in community and rebuild relationships. So that’s a really important piece to us that we learned from our folks with lived experience. So we only set up in village settings. Those villages, we have five dignity standards that we require our customers – which are predominantly cities, counties, and states – we require them to show proof that they will meet these dignity standards before we will ship the product to them. So we’re a very unusual manufacturer in that way. We don’t just sell product. We sell product and tell you how to use it. So if you don’t use it the way we want you to…

WENDY GROUNDS: We’ll take it back.

AMY KING: So we’re very unique that way. Right? When you buy a car, they don’t tell you how to drive your car.

BILL YATES: Right.

AMY KING: We tell people how to use Pallet shelters. So we like to do things different around here. So we tell customers they must provide 24/7 service provision onsite for the residents who are there with the intent that they move on. So this is not meant to be a substitute for permanent housing. We want to make sure that it’s not perceived as that, and that the intent is that the site is temporary, and the people temporarily live there to stabilize. So that requires service provision 24/7.

Residents must have access to hygiene services. So bathrooms, flushing toilets, running showers, and laundry facilities. Some of our sites are not in compliance with this one, and we’re working with them to get them in compliance because it’s a really important part of human dignity to have access to these things. Sites must address food insecurity in some way. So there’s a lot of ways they can do this: helping enroll residents with food stamp programs, bringing food to the site, providing cooking, whatever that looks like. But they have to address food insecurity so people don’t go hungry, and they have to have access to clean water.

Residents have to have access to transportation. So what we don’t want is cities taking villages and putting them way outside the city where people are then displaced from other services they need like healthcare, family reunification services, legal support. They need to be either close to the services or have access to transportation to get to the services. So that’s really important.

And then the last one is safety and security of the residents. So things like the site must be fenced and have appropriate lighting. We want residents to feel comfortable and safe there. Single or double point of entry where we can control who’s coming and going from the site so the already vulnerable residents aren’t preyed upon, that sort of thing.

So those are all things that are incorporated in our villages, and they’re required to be met in order for the village to maintain its occupancy.

Forming a Team

WENDY GROUNDS: Just hearing all the different parts of your organization, you must have a huge team. And I also saw that a lot of the people who are working for you, they once experienced homelessness. So tell us about how you’ve assembled your team.

AMY KING: Great question. So we do have a wonderful team here. I’m very biased, but we have a fantastic team of very passionate individuals who care very much about this issue. Again, we started the company with some folks with lived experience, and that was really the foundation by which we developed both the product and the model. So it’s a really important cornerstone of what we do here at Pallet. So today the vast majority of our staff have lived experience in homelessness, addiction recovery programs, or have had interaction with the justice system, or a combination of those things. So again, they’re bringing their experience of trauma and isolation to the table to help us do better at what we do.

Our leadership team has a lived experience cohort. Folks can apply to be part of it, and they do a six-month internship basically with our leadership team. We teach them how to run a company so they learn how to read financial statements, how to make decisions, how to use data for making well-informed decisions, that sort of thing. And then we also invite them into the discussion; and we don’t make decisions, organizational decisions, without their input, so that we’re making sure that that voice is centered.

Our people come predominantly through word of mouth. So they know we’re a friendly organization. We employ everyone. We don’t care what your background is. We have all kinds of offense types, as well. So we take violent offenders, we take sex offenders, we take people with drug histories, everything. So a lot of people come here because they know we’re a friendly environment, and we won’t discriminate against them because of their background. We have a wait list of people who want to work here, so we don’t struggle to find employees, which is nice compared to some companies these days.

And our senior leadership are people who tend to gravitate towards us because they care about this issue, or they’re very social justice-minded. Many of them have lived experience; some of them do not. But those that do not are folks who are really passionate about this issue and want to be helpful. So those people have come to us kind of naturally or through our networks, folks that just care about the issues.

Overcoming Obstacles

BILL YATES: You know, Amy, every project has obstacles that will try to undercut the project. And I cannot imagine the number of obstacles that you guys had to overcome. You could probably write a book about it, but could you just pick a couple obstacles and how you guys overcame it? Maybe share some advice to other project managers that are ready to pull their hair out or throw in the towel.

AMY KING: Yeah, we have so many really difficult obstacles. And yes, sometimes I do want to pull my hair out. And I will say it’s an ever-evolving thing; right? I mean, we’ve overcome lots of obstacles. But every time it feels like we overcome one, a new one pops up. So, you know, we’re working with a complex issue, a vulnerable population, and a very politicized circumstance.

And I think because of those things, and the ever-changing political environment around us in America today, and the polarity of our parties, I think, you know, we’re constantly struggling with political forces. And I’m not a political person. I didn’t study this. I don’t care that much about politics. And I’ve found myself spending a lot of time in Washington, D.C. and in state offices and in city offices. And I’m learning a lot.

But the primary barriers we face, I mean, there’s a few that we face everywhere. So one is NIMBYism. I mentioned that before. So community adoption and acceptance. And typically that stems from a place of ignorance and lack of understanding. And it’s not anyone’s fault. I mean, I used to be one of these people. I did not have a lot of experience with people who had experienced homelessness. There’s a fear that comes from the unknown.

So we have to spend a lot of time educating communities, introducing them to people who have moved on from homelessness and addiction so they can see what the outcome can be. There’s a lot of stigma that we have to kind of bump up against and let people feel uncomfortable, and then teach them how to get around that; right? So we do a lot of feeling-based stuff in our work there. That’s probably our biggest barrier.

And then other than that, it’s things like land availability. So finding resources to be able to build our sites. Funding. Funding sources are certainly a challenge. During COVID they were not because money filtered straight to cities to do the work that they knew needed to be done. And I wish that was a thing that happened all the time because we saw, not just for us, but we saw some really effective responses.

Mayors know what their communities need, and they don’t get funding directly normally. It filters through from federal to state to county to them. And when it went straight to them, man, they were moving fast. They were getting great outcomes. I mean, so we’ve been advocating for more of that because we were able to prove during COVID how effective mayors can be with money in their hands. So we deal with funding and the challenges of the bureaucracy of how funding is done for human services.

We really struggle with a lack of workforce in the field, so people who are willing to do mental health response and services. So educating around why this is important, how this is important, advocating for people with lived experience to get access to education and tools so that they can become those mental health workers.

And then certainly just the general political stuff. We bump into a lack of political will to respond to the issue probably more often than anything else. That is driven by a whole variety of things, and every community is different. So there is no blanket response. In order for us to get past those challenges, we’ve had to take a really personalized approach to every city and region that we enter. So we go in, we do a comprehensive needs assessment to determine what’s available, what’s needed, what the barriers are going to be. We power map who the decision makers are, where the money is, what the best path forward is to get this done fast. And then we help cities implement.

And we actually just created a new program called Path Forward, we’ve got some city peers, and they work with cities to help them put together comprehensive plans, not just for Pallet sites, but homelessness response in general. And that’s really helped us navigate some of these challenges. So from a project management perspective, identify the problem, create a strategy to resolve it, and then implement, implement, implement. Right? So it’s that simple, but it’s also not that simple.

BILL YATES: Right, right. It’s a known path. It’s just very tricky to navigate it.

Requests from Cities

WENDY GROUNDS: Do you have cities that reach out to you and say, “Hey, can you come build a village?”

AMY KING: Yeah, the vast majority of our sites to date, we’re at about 120 sites that we’ve deployed to date in 85 cities. We’re in 22 states. Most of those, the vast majority of those have come to us, have been inbound requests because someone heard about us or saw us on the news, or someone told them about us.

We do have a marketing team, and we do outbound marketing and sales to some extent now. But typically they come to us.

Overseas Market

BILL YATES: I thought I saw, when I was looking at the electrical that’s set up in the units, are you set up for the EU also?

AMY KING: Not yet. So we are actually working on, we have had some international interest. Well, I should say we just opened our very first site in Canada. So we’re really excited about that. And we’ve talked to some other countries, as well, and some European countries. So we are looking at expansion into international opportunities.

Our goal has shifted. I mean, when we first started, because of the crisis that we’re experiencing here, our goal was to end unsheltered homelessness in America. But as we saw the need and the response to the tool, we realized people are displaced everywhere, all across the world, for a variety of reasons; right? So it can be homelessness; it can be disaster; it can be geopolitical conflict and war; I mean, a variety of things. So we have since expanded our mission to include providing safe, stable places for people across the world to stabilize and grow and move on to the next phase of their life.

And that means we’re constantly iterating and looking for new products. So our current product that you see today, which is changing in about a week, is probably not the most appropriate product for international expansion. So we’re looking at what that product might be, again, centering voices of lived experience. So talking to people in refugee communities, trying to find out what their needs are and better understand how we can be of use and add value to their process.

The Goal to End Homelessness

BILL YATES: I’ve just got to hit the pause button and say, all right, we’ve spoken with the project manager from the Ocean Cleanup Project. Their very modest goal is to remove all the plastic from the ocean.

AMY KING: Very modest.

BILL YATES: Your very modest goal is to end homelessness in the world. That’s fantastic, Amy. I love it. I mean, what a mission; right? What a mission. Gosh.

AMY KING: I mean, I think it can be done. And that’s the thing that, when we first started this, and people still say it to me all the time, they’re like, “Oh, homelessness will never be solved in your lifetime.” And I always say, “Why? Why not?” I see no reason why we cannot solve homelessness in our lifetime. There’s plenty of resources out there. There’s a lot of really smart people who know how to solve this problem. And we’ve intentionally surrounded ourselves with those people. There’s all kinds of new construction and housing technology coming online all the time.

So whether it’s us or someone else or a collaboration of us and other people, we intend to achieve the goal. If we get in the way, we’ll get out of the way. The goal is still the goal; right? And it’s going to require all of us to solve this problem. But people should have housing. Housing is a human right. We believe that. And we started this company because we felt like housing was a human right. Does that mean everybody has it? No. So we have to figure out how to solve that. And there’s a big American discussion around affordability, which is a really important discussion.

But I would argue that our time looking at this in the past seven years with Pallet, we have learned that affordability is actually a lesser issue than access. So you can build affordable housing until the cows come home. But if people can’t get into it because they have a history, a felony history, or because they have an eviction history, or because, you know, whatever, fill in the blanks, it doesn’t matter. People aren’t going to be able to use it.

So housing, there’s this really popular American narrative which is homelessness is a housing problem. I 100% disagree with that. And I would very gladly argue with anyone who wanted to argue with me about this issue. A house, four walls and a roof, do not solve a person’s homelessness crisis. Giving them keys to an apartment does not solve their homelessness. You have to address the root cause issue. That person will end up homeless again. And this is why people continue to cycle through these broken systems, because we have allowed ourselves to believe through a perversion of the housing first methodology that providing someone a house solves the problem. It does not.

There must be services. There has to be community interaction. There has to be relationship building. People have to embed themselves in a community in order to resolve this long term. And we’ve completely ignored that and decentralized mental health services for decades. We have to address this problem, or this will continue. So I’ll get off my soapbox now, but thank you for letting me say that.

BILL YATES: That’s awesome.

“What I Wish I Had Known”

WENDY GROUNDS: So when you came into this, you didn’t have that soapbox. This is something that you have learned as you’ve worked this project. Other than that, what are some of the things that you wish you’d known before?

AMY KING: Ooh, that’s a good question. There are so many things I wish I’d known before. I wish I had known how hard the stigma would be to push past. I think I’m a person who has always been very open-minded and had a broad worldview. So it was easier, not easy, but easier for me to get past my own fears and misunderstandings around populations who had experienced homelessness, who had struggled with addiction, and who had been in the justice system. That’s not to say I wasn’t scared at first, because I was. And I absolutely was. But it took that human interaction to be able to get past it.

And what I’m finding is there’s not a lot of people who have that broad worldview or that open heart and mind to consider someone else’s experience. And I think we’re seeing it more and more now; right? I mean, as Americans, we’ve become even more isolated because of technology and COVID, of course, forced to this massive isolation. And that human interaction that overcomes bias, it’s not popular. It’s not talked about enough. It’s not demonstrated enough, that idea of how we build empathy; right? And it’s coming around more. People are talking about it more.

And I wish when we had started this that I had known how in opposition everyone would be to even talking about it, and so many people saying, “Well, it’s not my problem. If that person wants to sleep on the street, let him sleep on the streets.” My response to that has always been, “It is your problem because as humans we have this core innate connection to one another as humanity.” And even if we don’t publicly acknowledge it, when you walk past a person who’s suffering on the street, a little part of you dies inside and goes, “Oh, that’s sad that that person is living that way. That’s not right.”

You may not acknowledge it right away, but your humanity does not allow you to ignore the suffering of someone else. And if we could get people to understand that and really dig inside it and feel that, I think we would really change the landscape of responding to human suffering. People need help. We all need help sometimes. So that’s one thing.

The other thing I wish I had known was how hard it is to navigate the American government. And I’ll just put it right out there. It is so very hard, and it is way more challenging and complex than I ever imagined. Again, I’m not a political person. I didn’t study this in school. I didn’t care about it all that much. I mean, I voted and all that kind of stuff, but very ignorant about the inner workings of the government.

I now see the inner workings of the government on a regular basis at a local, state, and federal level. And it’s dysfunctional, super dysfunctional. And I’ll just say it. And as a business leader, I’m like, “Guys, we could be way more efficient here. Like why are we doing things this way?” But that’s not my job. So I wish I had known more about government and its essential part in human services because it does need, I mean, government needs to be at the table. They need to be there. But getting them to consider new ways of doing things or more efficient ways of doing things, more cost-effective ways of doing things, that’s hard. It’s way harder than I realized it was going to be.

Where to Next for Pallet?

WENDY GROUNDS: So what are some of the good ideas for Pallet? Like where do you want to take it next?

AMY KING: Yeah. Well, I’m excited. Like I mentioned that we’re launching a new product line that’s coming out next week. So super excited to see kind of what that does in terms of helping with some of the barriers we face. But in addition to that, we’re seeing this kind of evolving landscape around housing that’s moving in a direction that we don’t like and is from an equity perspective really alarming to me. Sort of think of it as like an idea for creating interim solutions that cities want to use as permanent. And I find that concerning. I feel like we’re on the path to creating the future slums of America. Because we already know that people who are experiencing homelessness, they’re already vulnerable, marginalized populations – people of color, people who’ve lived in poverty for extended periods of time, that sort of thing.

So think of this as what I’m afraid of is that we’re moving towards a modern-day version of redlining. And I don’t like that at all. So keep your eyes on things. We’re working on a possible concept to create some new home ownership opportunities for folks that are from marginalized communities. I can’t say more than that right now.

But we really want to encourage more housing justice, allowing people to get into the American dream, as it were, which I think has evolved as well. But wealth-generating tools, ways to build equity, integrating people, we can all learn from each other and help each other; right?

So mixed income housing, better community development and home ownership. We’ll be talking about some of those things with more intention in the coming year. So I’m really excited about that.

Access to Housing for the Homeless

WENDY GROUNDS: That’s exciting to hear because it’s not just access into housing, but you don’t want them to stay in the Palette village. They need access into permanent housing, you know, another step up.

AMY KING: That’s right. Home ownership and home entry opportunities have died over the years for a variety of reasons. But we’ve lost a lot of that entry-level home ownership stock. And as a result, you have people that rent their entire lives.

And certainly, you know, real estate is not the only way to get wealth generation. So the other thing that we’re doing a lot of and we’ll be talking about more is our workforce development model, and helping people who traditionally have not had investment accounts. Like all of our staff have 401(k)s. The vast majority of them don’t even know what that is or have never had one. And they’re in their 30s, 40s, 50s because they’ve been incarcerated for extended periods of time; right?

So helping people understand how to grow wealth in a variety of ways through your workforce community, but also through your homeownership opportunities. We’re going to be talking a lot more about workforce development and growing the workforce that’s needed in the trades industries, manufacturing and construction, so that we can build this stock of housing that we need that’s not just affordable, but also accessible and available for ownership for wealth generation. So all important things.

Intrinsic Motivation for the Project

BILL YATES: This is fantastic. This has been so fun talking with you, Amy, and hearing the vision and just picking up on the passion and the calling. You knew there was something there when you got started, and coming up with a solution. And then when you started to really engage with those that it was going to impact, I think the passion grew, and we’re sensing that and seeing it. What a great call to action. I think in terms of motivating team members, they have no problem.

AMY KING: We do have a lot of, like I said, really passionate folks, and they’re intrinsically motivated. And I will say, too, you know, I said before that I found the government to be dysfunctional, which is true. Well, I’m also seeing a big shift in government employees. There are a lot of really intrinsically motivated folks moving towards government that want to see it change. And it’s hard to change things that have been in existence for a really long time. I don’t blame them for getting to a dysfunctional state.

But I am very moved by what we call sort of this army of social justice warriors that we’re finding in government, in human services, in the business community. I mean, people, there are people everywhere who care about these issues and want to see people improve their lives.

And everybody can do that from their current place. I mean, you can be working at 7-Eleven and have an impact on somebody. You could be working at Microsoft or, you know, in the government, and you can have an impact on someone else’s life in a very real way. We want to motivate everybody. Everybody’s a stakeholder in this issue. And I think everybody’s trying to do better; but it’s hard to change old systems, really, really hard.

WENDY GROUNDS: Yeah. We were just talking about that earlier. Just because you’ve always done it that way doesn’t make it right.

AMY KING: Right. But getting people to try something different is really hard, especially in big federal agencies that have been doing it the same way for decades. That’s even harder. But it’s not impossible, and I’m going to keep trying.

WENDY GROUNDS: Well, we’re going to watch this space. We’re going to keep following.

BILL YATES: Yes.

Find Out More

WENDY GROUNDS: We’re going to keep an eye out for what you’re doing. If our audience wants to also find out more about Pallet and your work, where should they go?

AMY KING: Yeah, so they can go to our website at PalletShelter.com. We have all kinds of information there about our products, about our workforce model. You can also find information about Path Forward, our program that helps cities think holistically about homelessness response. And we have some great links to resources there outside of us to learn more about homelessness, as well.

BILL YATES: Thank you so much, Amy.

AMY KING: Awesome. Yeah, thank you. It’s really a privilege. I appreciate you inviting me on.

Closing

WENDY GROUNDS: That’s it for us here on Manage This. Thank you for joining us today.

To advance your career, you can check out over 65 online courses at Velociteach.com.

606 Views