It’s a great disservice to everyone, especially young people, that the stories that we often hear about the most accomplished entrepreneurs sound so effortless. The truth is just the opposite, even for visionary creative success stories like those of Mark Zuckerberg, Jack Dorsey, Howard Schultz, Wendy Kopp, and even the legendary Steve Jobs. Like any creative process, any entrepreneur who wants to invent, innovate, or create must be willing to be imperfect and make mistakes in order to learn what works and what does not.

It took Dorsey years of experimentation before he finally latched onto what ultimately became Twitter. Wendy Kopp started Teach for America, initially as a conference, on a shoestring budget after graduating from college. And Howard Schultz, while he had great foresight to recognize that Americans needed a communal coffee experience like those that existed in Europe, failed on his first try. As I wrote in Little Bets, when his first store opened in Seattle in 1986, there was non-stop opera music, menus in Italian, and no chairs. As Schultz acknowledges, he and his colleagues had to make “a lot of mistakes” to discover what would become the Starbucks we know today.

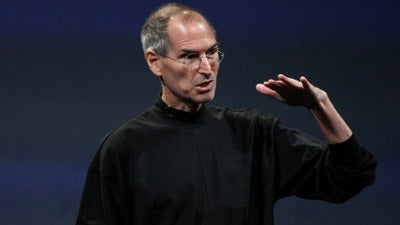

Despite what we may have read, Steve Jobs was no different. Here are five of Jobs’s greatest mistakes, all of which history shows he ultimately learned from:

1. Recruiting John Sculley as CEO of Apple. Feeling that he needed an experienced operating and marketing partner, the then 29-year-old Jobs lured Sculley to Apple with the now legendary pitch: “Do you want to sell sugared water for the rest of your life? Or do you want to come with me and change the world?” Sculley took the bait and within two years, Sculley had organized a board campaign to fire Jobs. Jobs himself would surely consider hiring Sculley as a great mistake.

2. Believing that Pixar would be a great hardware company. When Jobs was the last and only buyer standing in 1986 when George Lucas had to sell off the Pixar graphics arm of LucasFilms (for $10 million), he never expected the company to ever make money on animated films. Instead, as Pixar historian David Price shows in his excellent book The Pixar Touch, Jobs believed that Pixar was going to be the next great hardware company. Not even a visionary like Steve Jobs could predict what unfolded at Pixar, yet to his great credit, he supported cofounders Ed Catmull and John Lasseter as they pursued their dream of producing a full-length digitally animated film from day one. He protected their ability to make small bets on short films in order to learn how to eventually make a full-length feature film in Toy Story.

3. Not knowing the right market for NeXT computer. Although Jobs tried to spin NeXT computer as an ultimate success when the assets were sold to Apple in 1996 for $429 million, few in Silicon Valley agreed. The company struggled from the start to find the right markets and customers. If you haven’t seen the video about Jobs describing the vision for NeXT’s customers, you should watch it on YouTube. It’s clear that even Jobs was confused. In it he says, “We’ve had, historically, a very hard time figuring out exactly who our customer was, and I’d like to show you why.”

4. Launching numerous product failures. The Apple Lisa. Macintosh TV. The Apple III. The Powermac g4 cube. Steve Jobs was brilliant about understanding how technology vectors were evolving, yet even he screwed up royally, and often. The lesson that I take from these defunct products is that people will soon forget that you were wrong on a lot of smaller bets, so long as you nail big bets in a major way (in Jobs’s case, the iPod, iPhone, iPad, etc). Jobs was a market research group of one at Apple, which carries with it great risk, yet it should be noted that his batting average improved over time, which comes as no surprise to those who study the benefits of developing strong creative muscles though deliberate practice.

5. Trying to sell Pixar numerous times. By the late 1980s, after owning Pixar for four or five years, Jobs tried on multiple occasions to sell the company, just to break even on his investment, which ultimately equaled roughly $50 million. He shopped Pixar to, among others, Bill Gates, Larry Ellison, and numerous strategic partners and companies. No potential buyer bit. It’s a good thing for Jobs, and his legacy. He eventually engineered the sale of Pixar to Disney for $7.4 billion in 2006.

The lesson, it seems, is fairly simple: Even the great business visionaries and luminaries of our times often fail and have setbacks. Imperfection is a part of any creative process and of life, yet for some reason we live in a culture that has a paralyzing fear of failure, which prevents action and hardens a rigid perfectionism. It’s the single most disempowering state of mind you can have if you’d like to be more creative, inventive, or entrepreneurial. The antidote is to try a small experiment, one where any potential loss is knowable and affordable.

The revolution will be improvised.

This article was originally published by Harvard Business Review

Published: October 3, 2013

3050 Views

3050 Views