Sometimes a project can feel like a three-ringed circus. You are managing the schedule, the budget, and the requirements, and at the same time, you’ve got to consider the stakeholders, team members, and the organization.

In this Manage This podcast, we take a look at the early 20th century traveling circus to see how they kept the circus performing as a “well-oiled machine.” You can listen to the full episode here or some teaser clips:

WENDY GROUNDS: Welcome to Manage This, the podcast by project managers for project managers. I’m Wendy Grounds, and in the studio with me is Bill Yates and Danny Brewer. We’re excited to talk to you today about the circus. Our guest is Jennifer Lemmer Posey. She is the Tibbals Curator of Circus at the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota, Florida. And she’s been working with circus collections and the international circus community for 20 years. Jennifer’s also served as editor for Bandwagon, the Journal of the Circus Historical Society, and was an advisory scholar for the Smithsonian Folklife Festival celebrating the circus arts in 2017.

You may be wondering why we are talking about a circus when we are a project management podcast. If we listen carefully to the story of the circus, we tie in so many lessons for project management, from building community, to planning and coordination, for being resourceful.

BILL YATES: Some of you may be thinking, “My project is a lot like a circus.”

WENDY GROUNDS: That’s what we were thinking.

BILL YATES: You know, Wendy, the traveling circus back in the early 1900s resembled a small city. It’s like a traveling city. It entirely packs up and moves to another city every day or every few days. The performance and movement of the circus must have required great discipline and carefully executed planning.

But it was so impressive that the U.S. Army sent a number of officers to study Barnum & Bailey Circus for a week. The report the officers sent back praised the complex logistical operation of this massive project. Here’s a quote: “It is a kingdom on wheels, a city that folds itself up like an umbrella. Quietly and swiftly every night it does the work of Aladdin’s lamp, picking up in its magician’s arms theater, hotel, schoolroom, barracks, home, whisking them all miles away and setting them down before sunrise in a new place.” It is magical what they did with the circus. And there are so many tiebacks, so many points that we can connect with the projects that we run.

WENDY GROUNDS: Hi, Jennifer, welcome to Manage This. Thank you so much for being our guest.

JENNIFER LEMMER POSEY: Hi, I’m delighted to be here.

Meet Jennifer

WENDY GROUNDS: So we want to dig in and find out more about the circus. But you have a very interesting job. What was your career path? How did you become the Curator of the Circus at the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art?

JENNIFER LEMMER POSEY: There isn’t really a direct path to becoming a Curator of Circus, is there. I was very fortunate. I kind of wandered my way into this job. I was a student of art history, and I was very interested in folk art and cultures that make art. And I happened to have a familiarity with the Ringling Museum because I had gone to school close by. So I did an internship, knowing nothing about the circus, and really was so amazed by the culture, by the passion of all of the people, the artists that we see in the ring, but also the people that make the magic happen behind the scenes. And so 20 years ago I took what I thought would be a starter job cataloging circus collections. And I just fell in love with it, and there’s a new thing to learn every single day. So I’m still here after all that time.

The Golden Age of the Traveling Circus

WENDY GROUNDS: Describe to us, to set the scene of what we’re trying to do today, just describe what the golden age of the traveling circus is.

JENNIFER LEMMER POSEY: I will preface this with, depending on who you talk to, the circus had various golden ages, of course. But here at the Ringling Museum, in large part because we’re based so much on the collections of Ringling Bros. Barnum & Bailey of the early 20th Century, that was the time period that it had its winter quarters here in Sarasota. So our collections are very rich in that history, and we have a spectacular miniature circus that lays out what the circus lot was in that era. So that early 20th Century traveling tented show is one of the golden ages of the circus.

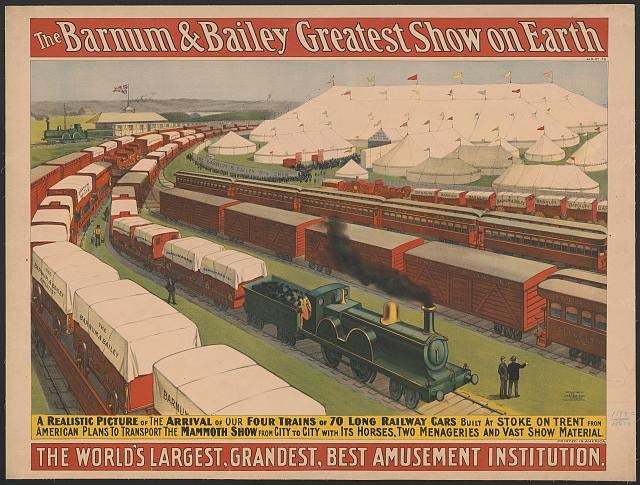

And in that time period, the circus Ringling Bros. Barnum & Bailey was the largest of the shows traveling really anywhere in that stage. In 1920 it was traveling on a hundred railroad cars, moving about 1,200 people every single day to put on a show in a new town. They were a tented city that, again, I can never say it enough, moved almost every single day. They performed in over 120 towns and cities across the nation during their season. So they had to keep moving, and the railroads were what really allowed that.

The Impact of the Railroad

WENDY GROUNDS: Can you tie in the impact that the railroad had on the circus?

WENDY GROUNDS: Can you tie in the impact that the railroad had on the circus?

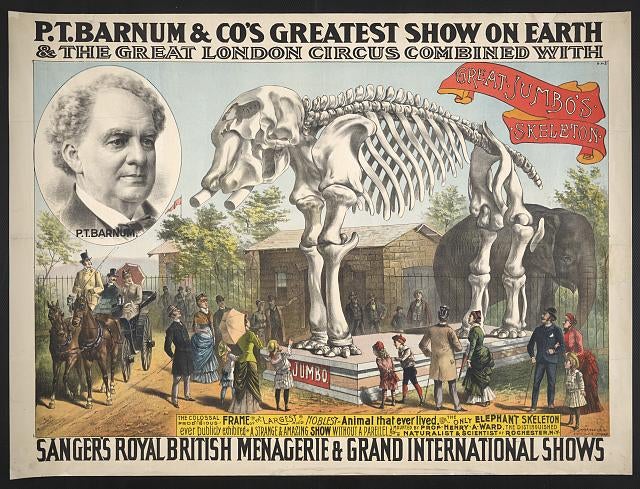

JENNIFER LEMMER POSEY: Absolutely. It’s interesting when you look back in circus history, P.T. Barnum, who always looms large in these fields, was the first to put the circus onto the railroad to travel every single day. He did that with a partner in 1872. At that point his show was only a one-ring circus, so it was a relatively small enterprise. Because he could play that many more audiences, because they could jump from town to town, he was able immediately to start growing more seats. He needed more seats to accommodate more people. When you expand the tent to add more seats, you have more performance space in the middle.

So the very next year after he went on rails, he expanded to a two-ring performance, added more acts so you could sell more tickets, made more money, grew his business structure that much more. And so it was because of the railroads, because of that transportation quality, that you could see the circus start to grow and grow and grow. And by 1881, it was Barnum and his partner by that point, James Bailey, who had the first three-ring circus, which is what we come to think of today.

The Project Manager of the Circus

BILL YATES: That is so fascinating. And I can’t wait for us to get into more of those details. But first, this is a project management audience. So who oversees all of this? Who’s the project manager of the circus?

JENNIFER LEMMER POSEY: The question of who is the project manager of the circus is so hard; right? Because when we’re talking about a circus like I just described, this huge traveling city, there are multiple project managers. So you do have a general manager. In that era, quite often it was one of the owners. So one of the Ringling Brothers or James Bailey was there on the lot, overseeing the whole global perspective. But obviously, at that scale, no one person could really have their eyes on every component.

So from that point it was broken down into departments. So there was the canvas department that oversaw setting up the tents. There were the concessions departments, the train department, the performance manager who oversaw the program itself, as well as the wardrobe department and the prop department that took care of all of those trappings of the performance. And that’s only a handful. I was looking at a route book for the Ringling Circus by 1950. And in that era, they had, it was over 35 different departments in order to allow the circus to keep moving as it did.

So no one project manager, but many very talented people who learned their craft, their contribution to the circus by being on the road. We don’t have a lot of documentation that spells out exactly how you do this job or what the expectations are because honestly, they’re moving too fast to refer back to documents. They have to have it all up here. And because of that, breaking down into multiple departments was really critical because everyone had a very specific role. They knew where they were supposed to be and what they were supposed to be doing at that time in the circus day to make the show move the way it should.

The Daily Schedule

WENDY GROUNDS: So the daily ritual. Can you kind of set the scene, what it would look like? They would arrive in town. They would have to offload from the train, get to wherever it is that the circus was going to perform. What did that all look like?

JENNIFER LEMMER POSEY: Circus day in the early 20th Century started for the circus community as early as about 4:00 a.m. And what I’m going to describe here really is about the Ringling show because it’s the largest. Around 4:00 a.m., the first section of the circus train would arrive in a town. And with it, it carried the boss of the canvas department, who would come with his crew and the equipment to stake out the lot.

So there I have to back up for a second; right? Even before circus day, someone from the circus, the advance man or the 24-hour man, had gone into the town at least a month in advance to secure the lot and to be able to order any supplies that needed to meet the show on that lot that day. So all of that logistical side was ironed out, contracted, whatever agreements were necessary were made. So the lot was there. The first section came in. They staked out how the tents would fit on that specific lot. And then the equipment started from that very first section of the train. This is again 4:00 a.m., 5:00 a.m.

First thing they do is set up the cookhouse and the dining tent because they need to make sure everybody’s fed to get the rest of the day going. So once that’s happened, then crews start raising all of the other tents. This era had eight major tents, the big top by far the biggest. It covered almost two acres of land to accommodate the performance area and all of the seating.

But there’s also the menagerie tent and the sideshow. There are horse tents, et cetera, et cetera. And so all of that has to be set up by these crews. Some of that equipment was on the first train. The second section of the train is coming in shortly behind. By 6:00 or 7:00 in the morning it’s there with the big top canvas and all the seating, all of the pieces to really raise the whole canvas city.

So that’s ongoing in the mornings. And they have to prepare for the third section that will come in with the props and all of the other final pieces of furnishings; and the fourth section of the train, which will arrive by mid-morning, depending on whether they parade. But you have to build the city before the people can come. So they really need the lot up and running by noon at the latest because they would have a 2:00 o’clock matinee. But you wanted to have the midway open so you could get people in to buy food and buy concessions. So all of that from about 4:00 in the morning until noon is the raising of this canvas city. 2:00 o’clock performance in that era. The show itself could run two hours or longer. They had concerts, they had theatrical presentations, as well as the ring displays.

You have that show. The staff and the crew eat between shows. And then before the 7:00 p.m. evening show begins, they’ve already started to break down things that came in the first section, the cookhouse and those early pieces of equipment. They perform the nighttime show. And this is what I think is the most magical. When you came out as an audience member from the evening show, say 9:00 p.m., you know, 9:30, most of the circus lot was gone. They’d already broken all of that down because it needed to be moving back to the railroad yard so that it would be on the section to move to the next town the next day. All of that was in one less than 24-hour period.

Logistical Magic

BILL YATES: I’m so glad you brought that up. That was so interesting to me, some of the research and reading I was doing before our conversation, Jennifer. I read that some of the guests would come out of the big top, and they were disoriented because now it’s 9:30, 10:00 o’clock at night. And everything that they had seen walking in, all the concessions and the other tents, are gone. So, like, wait a minute, which way do I go?

JENNIFER LEMMER POSEY: It’s impossible for me to imagine. And it’s this huge lot. And I do think that’s part of the magic of the circus is that this engineering feat, this whole magical world sprung up early in the morning and then is gone before you go to bed. You know, you just have this little moment that you get to experience all of that magic.

So many logistical organizational feats have to go into this because you’re exactly right. You think about really what I’m describing dates into the latter quarter of the 19th Century. So you don’t have a way to reach mass audiences like we do today. You know, no TV, no radio even at that point. So the advertising crew, the advance crew that went out and posted all of the bills started that process at least a month before the circus arrived.

And that was the first transformation of the landscape for people is all of a sudden old barns and fences are covered in beautiful, colorful paper with people doing things that you can’t imagine. So you have that for a few weeks, changing your world; and then all of a sudden there’s circus day, and that happens. I very much wish I could go back to an era where something like that really felt like magic, but the magic was only possible because of the whole community that was behind it.

Maximize Impact and Profit Margin

BILL YATES: The circus arrives in a city or a small town, and it could be that 90% of the town’s population is going to be at that show. You know, you could have 7,000, 9,000 people there. And to your point about the big top, they would set up bleachers and seating for 10,000 people under this one massive tent. Just amazing. Just amazing to think.

JENNIFER LEMMER POSEY: And they had to be adaptive, too; right? Because sometimes you actually would get more people, and who would want to miss out on a chance to go to the circus? So if the circus found that they could seat 10,000, but they had 12,000 people who wanted to pay them money to come see this show, they would find a way. So they called that a “straw house.” And what happened then, if they actually sold out all of the physical seating is they would literally spread straw down in front of the seating areas and accommodate more people who were willing to sit on the ground. Because it’s always that effort, you maximize the impact and the profit margin.

Leveraging the Business Model

BILL YATES: You know, another thing that just intrigued me was, of course, I’m looking at this from a standpoint of a project manager and thinking of the communication methods that we have today versus then, and all the work that the 24-hour man, the frontman would do. I love your pointing out the visuals, too. Okay, we can’t blast an email blast or a web page or a commercial on television, but we can put up posters to let communities know we’re coming. And, you know, there weren’t a lot of zoos back in that day in the early 1900s. So this was an opportunity for people to see exotic animals that they, you know, they’ve only heard about. So the draw must have been amazing.

JENNIFER LEMMER POSEY: Absolutely. And the animals were very important. When you look to the 19th Century, menageries originally traveled apart from circuses. But circuses, one, recognized that just logistically there was a lot of crossover, and within the business model you had, the talent of running these shows was moving between the two different forms. But more than that, many audiences who had in the early 19th Century some reservations about going to see a circus, going to see these transient people, performers who perhaps could be somewhat scandalous, anyone who had reservations about that was probably very willing to go to a menagerie because that was considered an educational opportunity, a chance to see something from a faraway place and to learn about the world. And so by incorporating the menagerie into the circus, it was a way to sell tickets and bring in a diverse audience.

Strategic Planning

BILL YATES: It’s fascinating to me logistically, too, the way they’d set the trains up. Specifically, this one has to be the last car because that’s the first one coming off. You know, and on and on.

BILL YATES: It’s fascinating to me logistically, too, the way they’d set the trains up. Specifically, this one has to be the last car because that’s the first one coming off. You know, and on and on.

JENNIFER LEMMER POSEY: The whole act of moving by train actually really was such a complicated feat because, you’re right, they had to think strategically about the order of the cars themselves, you know, what do we need on the lot first, what has to be there at the very end. But you also have to think of just about like the movement and what you can get through the railroad yard, how do you move everything and keep it safe when we look to the active unloading the circus train because it had to happen at a really quick pace to keep up with that day. And the men doing it were probably actually doing the most dangerous job of the whole circus day because these wagons weighed, you know, four or five tons by the time they were loaded up with equipment, came rolling down those runs at the end of the train at this crazy pace. And it was one rock, one thing out of place and that wagon could topple off, and it did happen that there were accidents in those – in that place. It was easy for someone to be hurt while unloading the train.

BILL YATES: Yeah. And it’s 4:00 a.m.; right? You know, they’re probably using torches to light. They don’t have the sophisticated lighting we have today.

WENDY GROUNDS: And they haven’t slept because they’ve been taking a tent down the night before, so.

JENNIFER LEMMER POSEY: You know, I didn’t even get into the accommodations on the train. But people talk about the magic of running away with the circus. But especially for the working crews, they would sleep in sleeper cars, you know, bunk beds lining the length of the car three high, and sometimes two men to a bed, if it was a big enough show, and they were just crammed in in every possible way. So the lot was actually often where they would rest. There were tents on the back lot behind the big top that were there for the working crew to go sack out on hay – again, you know, not anything fancy, but a quiet covered place to rest.

Planning Routes

WENDY GROUNDS: One quick question on planning. Planning is such an important thing when you’re running a project to make sure that ahead of time the planning is done properly. There’s a quote from John Ringling that we found, and he said, “Our business is in constant motion; but beyond saving time, our object is to avoid mistakes.” One of the things that I think would have been important was planning the venues. So how did they decide where they were going, and did they do this like the year before? Did they just repeat where they were going? What was the background to that?

JENNIFER LEMMER POSEY: The routing of the circus was absolutely critical to the success of each season. By and large circuses, once they were established, really could look to previous years’ routes and understand, you know, what had worked and what hadn’t, and just make tweaks. Because in that time period, traveling by rail, it was important to be very linear in your travel. You weren’t going to go from a town on the East Coast to the West Coast and back again. That made no sense with the resources they had.

So you picked your route. You wanted to start where the weather was good; right? You wanted to be in places where, one, it was pleasant for people to come to the big top. But you’re also thinking about it in terms of what are the resources of the community in that moment. In an agrarian-based society, you know, especially when you get out to the Midwest in the early 20th Century, they want to know that they’re coming into towns shortly after crops have come in because that’s the time period where people are going have some spare money and be willing to put out that cost to go to the circus. If you arrive just before that time, they’re probably too financially strapped to do that.

So you had to have a good sense of the economies of the areas you went into. It’s one thing we know about John Ringling, that he really was the advance man for the Ringling Bros., and he had a very keen knowledge of these trends. And part of that had to do also with his business dealings with the railroad. And so it’s all intertwined because the railroads are part of that whole economy. And so knowing where things are shipping from and what’s moving kind of gives you a perspective of how towns are doing. So you factor in that portion of it. You also factor in, is this town and its surrounding area large enough to fill our big top, you know, for two shows.

And then from there, how far do we need to go to once again have a population that would fill. You don’t want to jump so far that you’ve missed people. But, you know, you have to factor in just those distances in the populations, how receptive towns are. Is it a place that you are going to have an easy time contracting the lot? That became more difficult as you went into the 20th Century because towns were growing, and so having a large open space became less likely near a town center. And the further out you are from town, the less people you’re going to have. So you really had to have a keen sense of how all of the economies of America were shifting in a really big time in terms of the way we were growing our towns and cities.

Thinking Holistically

BILL YATES: This is so practical. I’m thinking of project examples, too, where there are times when I’m so focused as a project manager on me and my team and what we need and how we’re going to work best and I’m not thinking about the customer. I’m not thinking about the environment we’re going into. You know, many of the projects that I did were onsite at a customer location, and I wasn’t thinking about their availability. Many times I go into a meeting and say, okay, we’re going to show up on this date, and these are the team members that we need or the people that we need from your organization, the client, in order to get this done.

And they start laughing. They’re like, hey, that’s right in the middle of, you know, whatever, tax season; or we’re finishing up our annual reports. Or, you know, to your point, that’s when we’re harvesting. That’s the busiest season right before we harvest. So nobody’s going to be able to come when there’s no availability. So it’s so important to think holistically, to have that vision like John Ringling had, where he’s looking at it and going, okay, we need to talk to our customer first. We need to understand their environment and make sure that we’re showing up at the right time, when people can really engage.

JENNIFER LEMMER POSEY: Absolutely. It’s something I see in circus, both historically, but also even contemporary circus, is that recognition that you need all the voices at the table at certain points, or at least all the voices to be represented, you know, when you’re thinking about the big choices. So for the Ringling brothers themselves, they kind of dissected that work. John Ringling did the advance. His brother Al really was about what the program looked like, who were the performers going to be. Their brother Otto was the treasurer. He watched the money. So they divided those skills and then brought in, of course, managers who could implement and advocate.

The circus today, the Feld Entertainment who are relaunching Ringling Bros. Barnum & Bailey, part of their process is what they call a “white model,” wherein they run every aspect of the show in a form in a room with all of their department heads, as they’re styled today. In the past it was the train master. It won’t be a train master going forward. But the person in charge of transportation can say, well, it’s great that you want that prop, but how is it going to travel in the equipment we have. The person who worked with animals could advocate in the same way, that it’s fine that you want to have the horses go around the track in this way, but they’re going to be spooked by this, you know, this lighting effect that you have. Listening to every voice and letting each voice really have an area of expertise where they have the confidence to share and advocate is so critical.

Procurement and Inventory Control

BILL YATES: Jennifer, when I think about the procurement strategy and the inventory control that must have been necessary to pull this off, you’ve only got a 24-hour window of operation. How did the circus management and the project managers arrange the logistics of their supply chain to get food, to get materials and feed for all the animals that were there, all the other supplies that were needed. How did they arrange that?

JENNIFER LEMMER POSEY: no big box store that you can run to when you’ve realized you’ve forgotten something. Definitely preparing for a circus to arrive in any town was critical. And so the advance agent would go out when contracting the lot months ahead of the circus, and start to build relationships with the local vendors. Because they needed to be sure, from the moment the cook house was set up on the lot, 7:00 a.m., they needed, what was it, at least 3,000 or 6,000 eggs, I mean, just eggs, so that they could feed the people. And that doesn’t begin to touch on the things that you want on your plate besides eggs, and the need for feeding the animals, all of the meat and the hay, all of these pieces. So that advance man identified the vendors.

As the billing agents went through and put up posters, they usually had a man with them that was part of that advance and would go in and, you know, shore up those relationships, make sure that the right amount of food was going to be ordered and what time it should arrive, where it should be on the lot, how that would happen. The 24-hour man who was there a day in advance, you know, double-checked these things. And the circus really did rely on vendors they had relationships with. As you learn who you can trust. You learn who you know always comes through for you, and maybe even goes above and beyond. And they were very loyal to those people. So there was that kind of relationship, as well.

I’ve found in the years working at the museum that there is something so magical about circus that people love to be part of it in whatever way they can. So I think that must have helped. You know, it had to be pretty amazing to say as someone who was the local grocer, well, I had to supply the 6,000 eggs and the, you know, how many pounds of bacon that they needed, you know, to be able to tell your friends and family and show them the tickets because you probably got some free passes, that it didn’t cost the circus anything. They were performing. They gave away a few seats and earned a lot of goodwill and advance press. So that kind of playing to the fact that it is such an extraordinary thing, I believe, worked to their advantage in making sure that people really showed up and fulfilled their obligations.

Managing Resources

WENDY GROUNDS: That leads us to a very similar thing is their resources. So they would have had to have had equipment which was for setting up and for everything that they needed to do as a circus, as well as the animals and their performers. Those are all important resources of the circus. So what would they do in the event of illnesses or replacements and things like that?

JENNIFER LEMMER POSEY: The circus always has been very adaptive in all of these ways. They have to be self-sufficient because they are a traveling city, and they can’t be sure that they’ll find what they need anywhere else. So they traveled, for instance, with their own mechanical department and their own blacksmith department. They had forges that traveled with them in the era that they were moving with horses because you had to make sure, if you needed to reshoe a horse, it probably needed to happen very quickly. So all of those components that it took to run things were with the circus. There was somebody there with that expertise. And you know that there certainly is the chance of sickness. But the departments were generally built out in a way that was robust enough that, if one person was down and out, there was somebody who could cover at least for a moment.

Network of Support

And the other thing that I think is worth mentioning with circuses, it’s an undertold story, is early in the 20th Century the Circus Fans of America was established. And we think of fans, that sounds like such a lighthearted thing. But part of the reason that organization founded itself is because those individuals had grown to know the circus so well that they identified as part of the community, and yet they were living in different locations. And so if there was trouble, and the circus really needed some help in a town, they often would reach out to one of these members of the circus fans. So that was the person that would get someone to a doctor. Or if somebody was ill enough that they couldn’t go on with the show, they often would stay with one of these fans. So it was this network of support that underlaid and, you know, was in permanent spaces.

BILL YATES: That’s fascinating. I think of some of the projects that I’ve been a part of that have really had a big positive visible impact to communities. And I could see the value in that and being able to have those who are so supportive of the project, even though they’re not a part of the project team, they just want to help any way they can. And for the circus to tap into that, that’s great. That’s a great example.

JENNIFER LEMMER POSEY: And it’s that same idea that you find individuals who have talents that do lie outside of your business. Might not always be a physical contribution, but just to share some wisdom and insight. You can find those resources, and they can really add to whatever endeavor you’re trying to complete.

Communicating Lessons Learned

BILL YATES: Jennifer, there must have been, through the years, the leaders and the advance men, they must have come up with really robust lessons learned and risk management. You know, here’s a list of bad things that could happen when you go to this town, or when you go to this town. Here’s what happened last year. You know, three years ago we ran into this. They must have done a great job of not just having that in their head because they were smart business people who thought, okay, if I get sick, then somebody else needs to know what should take place.

So risk management leads me into communication, which is, okay, how did they communicate that with the other leaders of the effort? And how did they capture that information so that, if somebody did get sick, or somebody else – let’s say, okay, my wife’s having a child, and I need to go home for a couple of months. Go ahead and run the circus. All right. You’ve got everything in your head, Bill. So how did they gather some of that information and share it?

JENNIFER POSEY: The documentation of the circus in the early 20th Century is pretty sparse in terms of actual business documents. You obviously, you have the contracts and those kinds of things. But the day to day that happened in part, for exactly the reasons you just stated, because communication was so radically different. And for the advance crews, someone who’s out in front of the circus, the cost and the time it would take to communicate all of the information that they have gathered just wasn’t efficient for business at that time.

So we do know that many of the advance agents would keep a day book, and they would really record in there any kind of incident, you know, anything that was out of the ordinary or any specific costs, that kind of detailed information. They really maintained their own daybook. They used them as their own reference material. I have to imagine that they shared them perhaps with someone who worked in tandem with them that was apprenticing for that next step. But they weren’t necessarily returned to the business.

What communication did happen happened mostly via telegram in those instances where someone’s out and about. And so they’re very terse. You know, they say exactly that piece of information you need to know. “Got the deal on the hay.” “Will arrive at 6:00 a.m.” You know, that’s it. No depth of information there. So more than anything it was this oral tradition that you grew up in the business. You started as a young man. James Bailey is a tremendous example of that. He goes on to partner with Barnum, obviously one of the greatest businessmen in circus history. But he starts off as an orphan who’s run away and joined with a small show owner. And so he learns ground-up what it takes to run a circus by doing just the everyday work of it. And with each department, each advance in his career, he learned another aspect of the business until he was there at the very top.

Planning for Risk Episodes

WENDY GROUNDS: Bill mentioned risk. And the big thing in a project is how do you take care of risk issues? How did they plan for risk episodes? And are there any stories of times when a big risk incident would have happened?

JENNIFER POSEY: Obviously, risk is built into every aspect of the circus. It is inherently part of what we’re drawn to about it is the danger, from the unloading of the train, as I described earlier, to the actual performances in the ring. Everything in the day seems like a place where something bad could happen. And certainly for the business model, moving every day and trusting outside vendors for all of the resources you need also has lots of risk involved. So in every way the circus was facing that.

They had “fixers,” as it were. That’s what it was called, the person who traveled with the show and would deal with any run-ins if there was a question of whether elicit activities had happened on the circus lot, something had been done wrong, or someone had been pickpocketed, or shortchanged.

The fixer, who was usually an attorney, would be the person that stepped in and was the voice of the circus to make it right. And it usually was more of a matter of placating that, making sure that, if you could right the situation, you did. If not, can we give you tickets to the next show? Is it that level? Or is there, you know, does it require something more? So most things were dealt with that way. Obviously you get later into the 20th Century, I think the Hartford Fire is, you know, one of these perfect examples, 1942. A matinee show of Ringling Bros. Barnum & Bailey in Hartford, Connecticut, a fire was set, and the big top burned so rapidly that many people lost their lives. And that was a major court battle.

At that point the circus itself was an incorporated business, and so it was really this upper-level management that took responsibility for it. James Haley and others did some time in prison as a result of what was considered to be negligence, although in reality it was seen that the fire was set by someone outside of their control. So they did, as they got into the later 20th Century, I think when we as a country became more, started to become more litigious, face those battles. But I think there were a lot of gentleman’s handshakes in the early 20th Century that just settled these problems.

And for performers, just to kind of sidetrack on the nature of risk, the performers really understood every calculated risk in the acts they were doing. And because of that, many of the aerial performers, for instance, would never let anyone other than themselves or their immediate family rig their apparatus because they needed to know with absolute certainty that it was set just the way that it needed to be. You know, they would check everything. And accidents still could happen. But there was such a keen eye for the things that could go wrong, that they worked very hard to prevent them by noticing the details every single day.

Company Culture

WENDY GROUNDS: What was the culture like within the circus? Because you had so many different groups of people. You had the performers. You had the people who were just putting the tents up. How did they work together? Did they all eat together? Was it kind of like a family, or was it more like just a city?

JENNIFER POSEY: I love that you ask this question about how did they – how did they come together? Did they eat together specifically is an interesting thing to look at because, once you get to the very large circus like I described earlier, when it’s traveling with, over a thousand people, obviously you’re going to faction off in some ways. So the whole act of dining in the early 20th Century on Ringling Bros. show, the dining tent was actually divided in half. There was a wall, a canvas wall that divided it most of the year. And on one half it was the laborers, the men that were traveling with the show, that would raise the big top, that would feed the animals, do all of that work. And then the other half of it was the performers and the managers. And they were fed the same foods. They had the same resources.

But there was this division that was there, and it was a hierarchical organization in that sense. There was the recognition that these people contribute this way, these in a different way. Within those groups, though, the laborers tended to be a very transient group, aside from the bosses that managed departments. The men that, you know, actually did the physical act of lifting the big top could change every single year. But on the performance side and the managerial side, that those were faces that would be with the circus for decades because it was often families that performed. So you would see generations grow up there on the circus lot. They did keep within their family units. There was always that allegiance. But there also was a great deal of, cross pollination in terms of thinking about acts. Families merged into one another and married.

So there was a lot of interaction in that sense. In general is a sense with any circus, and it’s one of the things that I admire the most about it, is that the community of circus that makes up that show is with it and for it. It’s a phrase that they use. And the idea behind that is that ultimately, whoever you are, you know, whatever your background is, whatever your beliefs are, if you are in this project with me, if you are trying to make this outcome the best that it can be, just like I am, then we’re together, and everything else doesn’t matter. This is about what we’re trying to accomplish. I love that attitude. I think it’s one that we all could learn from. Put aside your personal differences and get this thing done.

The Satisfaction of a Common Purpose

BILL YATES: That speaks volumes, absolutely. And many times with our projects there’s a common problem we’re trying to solve. There’s a common need we’re trying to address. There’s something bigger than us. And that’s when we had to come together as a team to try to accomplish it. And even though we may have differences professionally, how we grew up or whatever, there’s something we can rally around. And that really speaks to me.

JENNIFER POSEY: I have to admit I think the day-to-day grind could get to people because that is a demanding life. But they keep coming back every season; right? Not necessarily the laborers. It’s the people that are there in front of the audience, the front of house; and the business side because I think that there’s such a tremendous puzzle to how do we do this. Even though we know how we did it last year, how do we do it, you know, with the resources we have this year, with the world as it is this year? How do we do this thing that we do so well? So I think there is that pride and joy in bringing something that’s always so tremendously special and that does unite an audience in a way that I don’t know of any other entertainment even today that can bring us together with as much joy as a circus performance.

Clarity of Roles Builds Trust

WENDY GROUNDS: I think some of the takeaways that I’ve got from hearing about the circus and how it applies to project managers and projects, is just the importance of their planning and their coordination, how they were so precise, and exactly knew what they were doing, and how resourceful they were. How they were able to use whatever that was coming up next in the next town. They planned their resources, and they were just so self-sufficient. And also having a good support network, I think that’s really an important thing for a project manager, as well, on your projects to make sure you have a great support network. And then the community, I love that, with it and for it. I thought that was so important that, you know, to have someone on your team that is with it and for it, and how important that is for project managers in their project to get a team culture that is so engaged.

JENNIFER POSEY: I agree completely that building that sense that everyone is engaged is critical to the success of projects in my own experience. Also, and you’ve touched upon this, but everyone in the project being very clear about their role. No question of am I supposed to be responsible for this because, not only does each one need to know their role, they need to know that their colleagues know what they can count on that person for.

And having that clarity of your role then I think builds trust, which is ultimately the foundation of circus, right, to trust that that catcher is going to be there to catch me when I fly from the trapeze. To trust that the big top is going to be up in time for the tickets I’ve sold. You know, you have to know that everybody is doing what we’ve expected them to do because any one piece of that falling apart cascades and could affect the project.

JENNIFER POSEY: It’s a stark lesson for me. I come from a creative background. I like learning lots of different skills. I love knowing all the different parts of a project I’m working on. But as I’ve matured, and as I’ve taken on other responsibilities, I’ve recognized that the best thing I can do to accomplish a project is define really not what I’d like to contribute, what I can contribute, and then identify that with my colleagues; and know that you’ve filled out all the pieces of the puzzle, not that you think you can accomplish it, but that you now know how you’re going to do it.

Find Out More

WENDY GROUNDS: If our audience wants to find out some more about the museum, or if they’ve got questions for you, where’s the best place for them to go?

JENNIFER POSEY: Best place to learn more about the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, which is where I work, is Ringling.org. You’ll find there that the museum complex is a circus museum and more. We were founded by John Ringling in his later years. And he actually founded a museum of art with an extraordinary collection of baroque and renaissance artwork which has grown now to encompass many diverse areas of the arts, as well as his historic home here on Sarasota Bay. We also have many of our collections online so people can see posters and photographs from the history of the circus. And there are links within that website to be able to contact staff members with questions.

BILL YATES: Thank you so much for your time, Jennifer. One of our instructors stumbled into your museum and was blown away, and said we need to have a conversation with the historians there because the more he thought about it, the more he was impressed by what these people pulled off, the incredible extraordinary planning every day, and having to deal with different situations every day that would pop up in the world of the circus.

JENNIFER POSEY: I’m so delighted that he had that experience because that is one of the things that I come back to all the time is just how much we can learn today from what the circus was. A lot of things have changed. You couldn’t work people the way the circus worked people. And, you know, the labor laws are very different for good reason. But it’s more than that. It is about the dedication and the teamwork and ultimately the project management that made it all possible. And it is an extraordinary story, and I feel very privileged to be part of sharing that.

Closing

WENDY GROUNDS: That’s it for us here on Manage This. To advance your career further, check out our online courses at Velociteach.com.

Thank you for joining us. Until next time, keep calm and manage your circus.

Photo credits: Library of Congress

1184 Views